Charles Chaplin and Oona O’Neill’s love was one of those called love at first sight. When they had four children, they had to exile themselves from the United States and settled at the top of a town called Vevey, on the shores of Lake Geneva. We visited the house where they spent almost 30 years, which is now converted into an interactive museum that pays homage to the creativity of one of the greatest geniuses of the 20th century.

Love in wartime

Truman Capote said of his friend Oona O’Neill, “She had only one flaw. She was perfect. Other than that, she was perfect.” Oona was the daughter of the American playwright Eugene O’Neill, winner of the Nobel Prize, and from a very young age, she was considered a celebrity among the New York intellectual elite. She loved to prolong afternoons at the legendary Stork Club (where she was named “Debutante Number One” of the 1942-1943 season), even if it meant sipping cups of tea with milk, as evidenced by the photos.

You’re going to meet a man older than you, and you’re going to marry him,” said Orson. “You’ll meet him very soon.

One of those nights, she met J.D. Salinger, who must have thought the same thing as Capote and fell hopelessly in love with her. He was 22 and she was 16. The budding writer made the imprudence of enlisting in the army and heading off to fight in Europe, from where he sent love letters, thinking that the image of a sweet soldier would soften Oona’s heart to the point of ending the letters in tears. But alas, while Salinger witnessed the horrors of the war that would haunt him forever, Oona accepted an invitation to dinner at Orson Welles’s house.

Actor Charlie Chaplin and his wife Oona at Schiphol Airport, Amsterdam (June 1965). Photo Joost Evers/ Anefo

Between dishes, he realized that she wouldn’t want anything more after dessert and asked the host to read her palm: “You’re going to meet a man older than you, and you’re going to marry him,” said Orson. “You’ll meet him very soon.” And so it was. While Salinger dodged death, Oona fell in love in Los Angeles with the most famous filmmaker of the moment, the great Charlie Chaplin, who wasn’t at all frightened by the age difference.

In fact, when he found out that Oona was 18, he subtracted his 54 years and thought: “Normally I could be the father of my actresses, this time I could be their grandfather.” He would later write, “Beauty is the only valuable thing in life. Those who find it have found everything.” A year later, he would become the fourth and final wife of the creator of Modern Times. Something Salinger found out by buying a newspaper in Europe and seeing the headline.

The story is well-known, but it has been best told by Frédéric Beigbeder in his extraordinary book, Oona and Salinger. Chaplin and Oona were married from ’43 to ’77. They had eight children. Salinger returned from the war and wrote the masterpiece called The Catcher in the Rye. Then he retreated, as if the phrase by Eugene O’Neill saying, “writing is my vacation from living,” was his own.

Charlie Chaplin with his wife Oona and their children.

In 1952, victim of a textbook witch hunt, Chaplin was repudiated by the United States. Accused of being a communist and invited into exile in Switzerland, where he settled with Oona and the four children they had at the time.

All of this crossed my mind during the journey from the Palace Hotel in Montreux (the hotel where Nabokov went to spend an afternoon in 1961 and ended up staying 16 years. Something that, if you know the place, lacks all merit) to the Manoir de Ban. Where Oona and Chaplin lived until the end of their days and what is now known as Chaplin’s World. An immersion into the genius’s universe who, without saying a word, spoke to everyone and made them laugh (and cry). Chaplin, who was an abandoned and hungry child, was able to settle scores with life to some extent. But despite the wealth he accumulated, he never stopped fearing poverty. There he is: a nobody who managed to belong to everyone.

Exile and life in Switzerland

The Manoir de Ban is a building from 1840, the work of the architect from Vevey Philippe Franel, built by order of Charles Emile Henri de Scherer, owner of the estate. It is located in Corsier sur Vevey, at the top of Vevey, and is surrounded by a park overlooking Lake Geneva. Neoclassical in style, it is listed in the Swiss inventory of cultural assets.

We have a beautiful house of thirty-six hectares that protect the charming town of Vevey, where Rousseau and Courbet lived and worked for some time. The views of the lake and the distant mountains are ineffable.

A few days after their arrival in Switzerland in December 1952, on the advice of their chauffeur, the couple stopped at the heights of Lake Geneva and visited the property, enchanted by the house, the trees, the garden, and the views.

“Manoir de Ban”, the estate where the Chaplin family lived in Corsier-sur-Vevey (Switzerland). 2016 Chaplin’s World™ © Bubbles Incorporated S.A. All rights reserved.

In one of the letters displayed, written by Chaplin to the American playwright Clifford Odets, he gives a good account of the romance they would end up living with this landscape: “We have a beautiful house of thirty-six hectares that protect the charming town of Vevey, where Rousseau and Courbet lived and worked for some time. The views of the lake and the distant mountains are ineffable.”

Chaplin’s World

The idea of a large museum dedicated to Charles Chaplin and his work was born from a meeting in the year 2000 between the Swiss architect Philippe Meylan and the Quebecois museographer Yves Durand, who agreed to preserve the essence of what was once a family residence.

In the tour of the Manoir and the Studio, there are over 30 wax figures created by Grévin of Charlie Chaplin, Oona, actors from his films, and more characters. © Bubbles Incorporated S.A. All rights reserved.

Chaplin’s World is divided into three thematic spaces: the studios, the mansion, and the gardens. Before the visit, a documentary with memorable scenes of the richest Tramp in the history of cinema is shown in a cinema room.

Charlie Chaplin was also a musician and composer; he loved music so much that he spent his first hard-earned salary on a violin. Self-taught, he also learned to play the cello before turning to the piano. ‘Music Times 2020’ exhibition at Chaplin’s World © Bubbles Incorporated S.A. All rights reserved.

The studios recreate sets and scenery from films such as The Kid, a moving autobiographical portrait with the shadow of Charlie’s complex childhood in the London neighborhood of Lambeth, where he was abandoned by a mother who had previously been abandoned by her husband. He was also an actor and singer in the Music Hall, and where the Chaplin Bar is located today.

One also empathizes with the universe of Modern Times and The Gold Rush, and of course, one can sit in the chair of the Jewish barber persecuted by the regime of Adenoid Hynkel, The Great Dictator, a moment in which one remembers that Hitler and Chaplin were born in the same year, 1889, with barely four days difference.

Charles Chaplin in ‘The Great Dictator’ (1940) 2016 Chaplin’s World™ © Bubbles Incorporated S.A. All rights reserved.

Of course, one cannot overlook what is probably the scene that Chaplin repeated the most times (it is said more than 500 takes) with the beautiful and blind flower girl, Virginia Cherrill, protagonist of City Lights, an endless shoot of which much has been written. Edna Purviance also appears in The Immigrant, Buster Keaton, and the fearsome Eric Campbell.

Both the president of the Chaplin foundation, Michel Chaplin, son of Charlie and Oona, and the project’s promoters, have wanted to emphasize Chaplin and Oona’s connection with the community and their efforts to maintain the not always simple family harmony in this Vaudoise Riviera.

In the museum’s facilities, we also find the restaurant The Tramp, located in the heart of the Manoir park. © Bubbles Incorporated S.A. All rights reserved. Oona and Chaplin: eternal love

Oona and Chaplin: an everlasting love

The aura of legend is what allows Chaplin to be reborn every day within these walls. Thus, Meylan and Durand affirm: “Life in the Manoir was quite cheerful, Chaplin playing jokes on the children, regularly clowning in the shade of the fruit trees in the garden, trying to communicate using the pantomime language…”

Charles Chaplin with his wife Oona and their children (from left to right) Geraldine, Eugene, Victoria, Annette, Josephine, and Michael. (April 1961) © Associated Press photographer

“The family had its customs, like the Saturday barbecue prepared by Chaplin, the swings, the swims in the pool, where the children’s friends came, the screenings of old Chaplin films on Sunday afternoons, with Oona handling the projector and Charlie in the background, fearing not to continue making people laugh.”

They also remember ball games, birthday parties, and the Easter egg from American Halloween. Apparently, Charles Chaplin was seen walking the pedestrian streets of old Vevey dressed in gray flannel and a white shirt, silk handkerchief, and hat.

Work is life, and I love living.

He and Oona liked to go to the market, walk along the shores of Lake Geneva, where they must have tired of seeing the excellent Villa “Le Lac” that Le Corbusier designed for his parents in 1923, and go to the Rex cinema in Vevey. He also made sure to learn about the history of Château de Chillon, where Lord Byron was imprisoned and where he was saved to write poems.

“Work is life, and I love living,” Charles Chaplin believed. Since he began his Swiss exile, he could hardly add two more films to his filmography. Although, he did write his famous autobiography here.

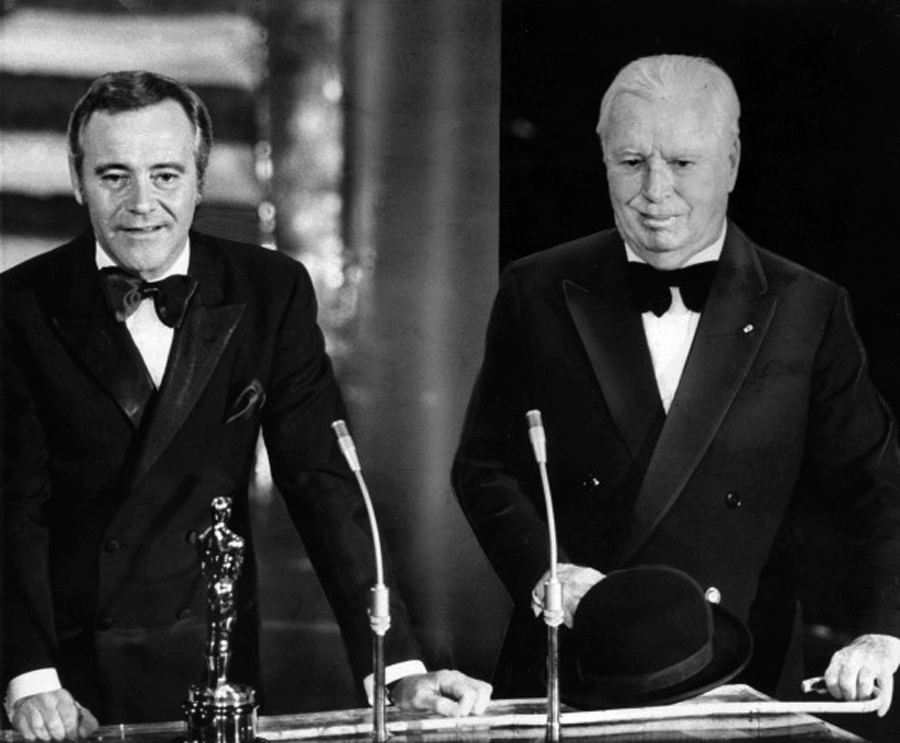

In the living room where old family films are screened, one sees a sensitive and troubled Chaplin, enjoying his children and Oona in his own way. In any case, the most exciting memory is the historic twelve-minute ovation with which Chaplin was received at the 1972 Oscars ceremony, when he was finally honored with an Academy Award for his “immeasurable impact on the transformation of Cinematography into the art of the 20th century.” And his fleeting return to the United States crystallized, a detail that symbolized Hollywood’s forgiveness for the shameful expulsion to which he was subjected.

Charlie Chaplin receives the Honorary Academy Award from American actor Jack Lemmon. © Copyright Associated Press photographer.

Beigbeder recounts that in front of the grave where Oona and Charlie are buried (not far from the house), he listened to the song Scarborough Fair by Simon and Garfunkel. A medieval-style song that defines a courtly love relationship, the love of a knight for a lady whom he never sees.

“For a man, happiness comes when a woman frees him from all other women; suddenly he feels so relieved that he feels like he’s on vacation. Charlie Chaplin just needed to look at Oona to feel light.”

“Mutual love is blissful but commonplace. Courtly love is painful but noble. Oona and Chaplin are a courtly love story. They are the most successful marriage I know,” Beigbeder asserts in his fabulous book. Before adding that “for a man, happiness comes when a woman frees him from all other women; suddenly he feels so relieved that he feels like he’s on vacation. Charlie Chaplin just needed to look at Oona to feel light.”

For the French writer, whose favorite novelist was always Salinger, “The Catcher in the Rye would be a substitute for City Lights, replacing the bowler hat with a cap. The purity of children, the corruption of adults: Chaplin’s films speak of nothing else.”

The graves of Charles Chaplin and his wife Oona Chaplin, in the cemetery of Corsier-sur-Vevey, Switzerland.

Chaplin died on Christmas morning in 1977 in this same mansion in Vevey. Later, Oona bought a duplex on 72nd Street East in New York. To escape the memories, to drink, to talk about how to stop drinking, and about her return to Switzerland. When she met Truman Capote, who surely still thought his friend was perfect.

Images courtesy of Chaplin’s World

Route de Fenil 2

CH- 1804 Corsier-sur-Vevey

Suisse