On the occasion of the centenary of Eduardo Chillida’s birth, we talked to his son Luis about how this great artist understood sculpture and life.

Luis Chillida is the seventh son of the eight children Eduardo Chillida had. And although we don’t need much of an introduction to talk about his father – the great sculptor of space and time – it is necessary to situate this interview in the artist’s centenary.

Luis welcomes us to talk about his father’s work and the recent collaboration between the Chillida Leku Museum and the Barcelona carpet brand Nanimarquina.

As manager of the Chillida Foundation, what can you tell us about this collaboration with Nanimarquina?

We have been collaborating with the brand for twelve or thirteen years. A total of eight series have been made and each one of them is limited.

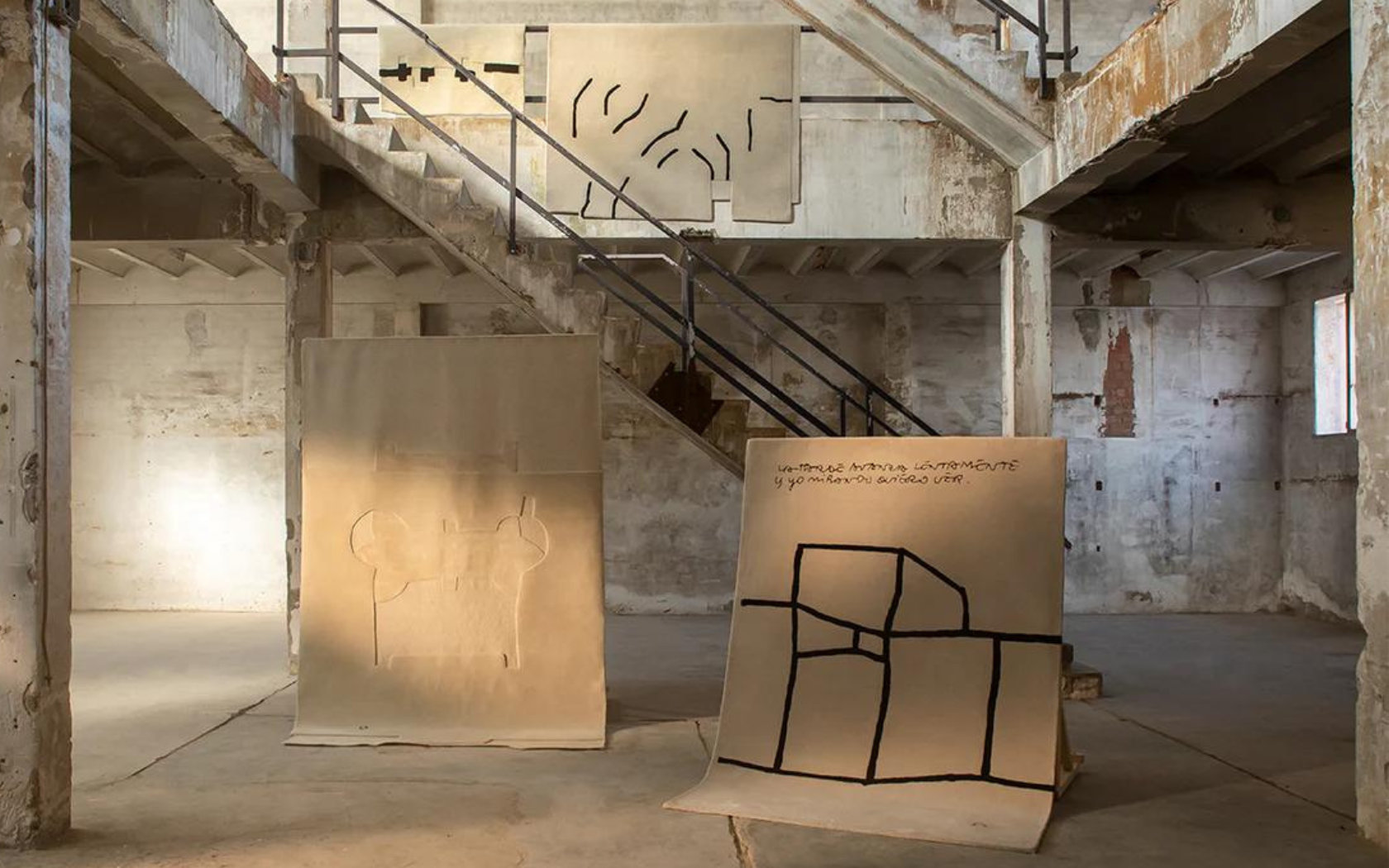

Part of the Chillida rug collection by Nanimarquina.

My brother Ignacio has been doing all my father’s graphic work since the late 1970s and is responsible for editing and working with the designers.

My father liked reproductions of his work but in a practical sense. Just as he never accepted reproductions of sculpture and three-dimensional work, he did with graphic work and tension work. In any case, when you have had an artist in your family, you always think: “Would he have liked this?

My father talked about his work in the sense of a spiral; a spiral in which he felt that his creative universe made him pass through places he had already passed through ten, fifteen or twenty years before. He said that each time he passed, he passed at a different height. There was an evolution within his own world.

“During his lifetime, my father did not think about recognition. When he finished a work, that work ended and he focused on the next one. It was the work itself that defended itself”.

View of the outside space of the Chillida Leku Museum. Editorial credit: Iñigo Santiago.

What other collaborations has the Foundation done on the occasion of Chillida’s centenary?

The temporary exhibition A conversation: Chillida and the arts. 1950-1970 at the San Telmo Museum.

(Helena): as part of the celebration of the centenary of Eduardo Chillida’s birth, the exhibition presents the artist’s creative universe within the framework of the artistic culture of his time, focusing on the first two decades, between 1950 and 1970. It was at that time that the sculptor defined his aesthetic ideals and his plastic imaginary. Both would remain with him for the rest of his life.

In order to commemorate this centenary, the San Telmo Museum has brought together more than one hundred works of art. A selection in which Chillida’s works dialogue with those of other artists and which embraces disciplines such as experimental theatre, photography, dance, film and fashion.

The exhibition is framed within the broad fabric of ideals, concerns and artistic experimentation that took place in the plastic arts, philosophy, architecture, dance, photography and music between the 1950s and the 1970s. A decisive moment for reconstructing the narrative of modernity after the tragedies of war. In this context, the exhibition presents Chillida “in conversation” with the artists of his time: Picasso, Miró, Arp, Julio González, Giacometti, Millares, Moore, Beuys, Aurelia Muñoz, Cartier-Bresson and Martha Graham, among many others.

(Luis): During the centenary we worked a lot on the concept of “meeting places“, which is the title of several of my father’s public works. In total he made some 1360 sculptures.

Works by Eduardo Chillida at the Chillida Leku Museum. Editorial credit: Iñigo Santiago.

“He liked to meditate on things, to drain them. Time was very important to him, as well as working on what you hadn’t done. Sometimes I have witnessed how ten or twelve years have gone by since my father started a project until it was finished. It was a question of each thing needing its time”.

Chillida was a creator of places and one of the artists who pioneered the concept of public space. How did he understand the concepts of place and public space?

The concept of place was very important to my father, as it is closely related to everything that surrounds him. Sculpture generates a place, especially here in Barcelona, like the one in Plaça del Rei.

He was interested in the idea of generating that place where people gather. He thought a lot about the place and about the work having an appropriate scale for that place.

For example, my father worked with the philosopher Martin Heidegger and they did a book called Art and Space in which Heidegger said that when you approach a place to act on it, in a certain way the place changes. For example, when the work Comb of the Wind was created, I remember I was 13 years old. By creating the sculpture, a place was generated that already had its own autonomy. Hence my father’s great interest in public works, because they belong to everyone. He was a forerunner in the concept of public works.

Eduardo Chillida next to the work Comb of the Wind, 1977. Editorial credit: J. Uriarte.

Do you think that the environment in which he grew up and developed his work was key to his understanding of space?

Undoubtedly. He said of himself that he felt like a tree, with its roots in the earth and its branches open to the world.

In his conception of public space there is a desire to vindicate a certain utopia. This is very much reflected in Chillida Leku. How did he construct that utopia?

Chillida Leku, as it was something that depended directly on him and my mother, was not so much a utopia. However, for me there were other projects that were clearly a utopia, such as Tindaya, in the Canary Islands.

«When you have had an artist in your family, you always think: “Would he have liked this”?»

When he worked with stone or alabaster, he used a natural block of granite to introduce space into the material. And then one day he dreamt of a utopia, which was to reach an agreement with a stonemason who would exploit the mountain and instead of extracting the stone, destroying the mountain, he would go inside and create a space inside the mountain for everyone. A space that had the illumination of the sun and the moon. This is what he tried to do in Tindaya. In the end it was not done because it was too complicated. For him, this was his utopia.

Work Arco de la libertad. Editorial credit: Mikel Chillida.

Which work would you say was the most important for him?

For my father every work has been his favourite and the most important while he was doing it.

In my haste I would say that there have been two very important works in his work. The first is Peine del viento, in San Sebastián, which was inaugurated when it had been 30 years in the making because at the time it was inaugurated it was not understood. It was a work ahead of its time.

The second is Elogio del horizonte, a work in Gijón. My father always believed that the horizon was the homeland of all men, especially those of us who live by the sea. He wanted to pay tribute to the horizon and began to think about it around 1975-1980. That place in Gijón was an old military fortress. Then he began to realise one thing: all the places that seemed suitable to him were military, because the military had always wanted to dominate the horizon.

__

The more personal side…

What is the style you like the most?

Within art I think that every artist has a style, and sometimes there can be a style that you like or that interests you without it being exactly the one you thought you would like.

A specific artist

Very influenced by my father, Brancusi.

Do you collect anything?

I have art collections.

A country you would go back to 100 times

Euskadi.

A pending trip

All trips are interesting, but I have none pending.

A daily habit

Quit smoking.

A hobby

I am a car and motorbike driver, and that is my great hobby.

A colour

Blue.