We talk to Llucià Homs, gallery owner and cultural consultant, about topics such as NFTs, or Non Fungible Tokens, digital crypto-art pieces to whichblockchaintechnology is applied and which have had a profoundly transformative impact on the art world.

Llucià Homs is fascinated by the world he lives in. Part of his work consists of keeping his curiosity, his capacity for fascination and his nose for the new intact. The NFT (Non Fungible Token), which have transformed the art world, are an example of this.

Homs’ curriculum vouches for this: gallerist, art dealer, curator, cultural consultant and journalistic disseminator. Homs earns his living by keeping his eye trained to “buy, sell, decode and explain” contemporary art.

In 1993 he opened his own gallery in Barcelona, where he was also director of La Virreina Centre de la Imatge. Resident in London, he has contributed to launching cultural initiatives such as the think tank of art exhibitors and sellers Talking Galleries. He is also a regular contributor to the digital magazine Hänsel i Gretel* and the Loop Festival, and a regular contributor to publications such as the newspaper La Vanguardia. These days, Homs admits to being somewhat perplexed by a new phenomenon that, in his opinion, “is bringing about a change of paradigm, we don’t know if it is irreversible in the art market”.

These are the so-called NFTs, which in 2021 will already exceed 3 billion in sales.

“This is a very specific type of digital art that has burst onto the scene in recent years and is drastically transforming the business of buying and selling art, which had hardly changed in essence over the last century and a half”, Homs tells us during a relaxed chat on the terrace of the AP House in Barcelona.

Llucià Homs during the interview on the Audemars Piguet terrace.

Disruptive digital art

NFTs have transformed the art world. Experts didn’t see it coming because “they lacked the intellectual and conceptual tools to value something that is radically new, a type of collector’s piece that is the fruit of technological manipulation and whose market value depends on factors that have little to do with artistic excellence as we usually understand it”.

As Homs explains:

“NFTs are bought, often at very high prices, by very young collectors who have enriched themselves by speculating in cryptocurrencies”.Who have become rich by speculating with cryptocurrencies and see them as a future

them as an investment for the future”.

From an artistic point of view they seem “trivial, they are mostly pieces of rather trivial contemporary graphic design“. However, Homs doesn’t rule out that this new consumer product related to digital art will one day find “its Banksy or its Marcel Duchamp” and make a qualitative leap that will allow it to find a place alongside Pollock or Mondrian in the halls of the MoMA: “The paths of art are inscrutable”, he notes with a certain scepticism, but “for the moment the NFTs have risen to the top of the market”:

“For the moment, the NFTs have subverted the market by creating a new and very lucrative sales channel. A new and very lucrative sales channel, often outside of galleries and outside galleries and fairs”.

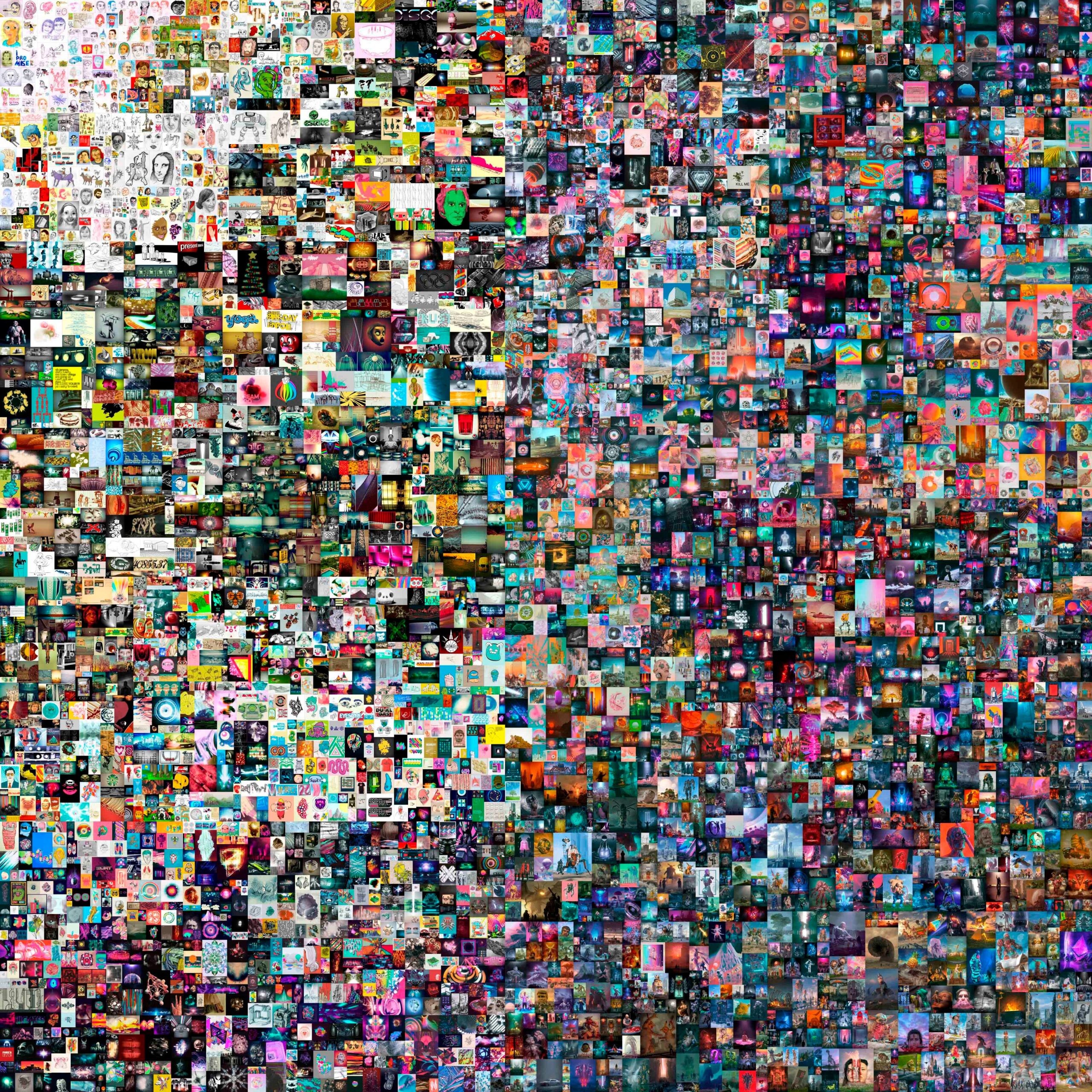

It remains to be seen whether “it will end up being a passing fad, a speculative bubble that will burst in the medium term, or the pioneer of a series of profound developments that we will have to get used to in the coming years”. The most expensive NFT to date is a collage of 5,000 pre-works by digital artist Mike ‘Beeple’ Winkelmann. It was auctioned at Christie’s last September and ended up selling for $69 million, a figure, according to Homs, “only within the reach of contemporary artists as sought after as Francis Bacon, Jeff Koons or David Hockney”.

NFT de Beeple Everydays “The First 5000 Days”. Cortesía de Christie’s

A disconcerting moment

Has the art market gone mad, unable to adequately process and digest the arrival of a generation of collectors with new values and alien to any previous tradition? Homs recognises that “we are living in a disconcerting moment”, but prefers to take this “radical disruption” with a certain caution:

“Art has never been alien to speculative dynamics. Art bubbles probably already existed in ancient Rome and they certainly existed in Renaissance Italy. We will have to see what happens with the NFTs in the medium term, but for the moment they have forced us to reconsider many things we took for granted, and that seems to me to be very healthy”.

For the cultural consultant, we live in an exciting era in which change is happening at breakneck speed. Even the pandemic has accelerated these changes “by demonstrating the viability of virtual auctions, which have become exciting spectacles with the capacity to attract new profiles of collectors”. At the same time, “it has shown that online galleries and virtual fairs had become obsolete and needed a profound technological renovation”.

New market niches have also appeared in the social networks, although for the moment relatively modest amounts are being moved in them”. And there continue to be curiosities that scandalise the layman, such as the “virtual” artist Salvatore Garau’s sale of a non-existent sculpture for 15,000 euros. For Homs, this latest piece of news is “of little relevance, it goes no further than a simple anecdote”. It is not the first time that an invisible piece of art has been exhibited or sold, an operation that can be interpreted “as a swindle or as a performative act, but not as a symptom of the shortcomings of the art market”.

Understanding the difference

In his opinion, a cultural consultant has the responsibility to explain to those interested in contemporary art that “Salvatore Garau is an anecdote and Banksy or Maurizio Cattelan, the one with the famous banana stuck to the wall with an elastic band, are a category, because they have a value”.

Banksy’s work “Girl with Balloon”. Courtesy of Sotheby’s.

He himself was trained to understand this difference and to be able to transmit it: “Let’s say that I am a gallery owner almost by biological imperative”. He tells us, “my father opened a gallery in the 70s and I remember myself in Vic, when I was just seven or eight years old, accompanying him to the studio of a local artist to take a look at his work”. He then went on to study law, business management and, finally, a postgraduate degree in media art, bringing together the set of qualities he considers basic in the professional context in which he moves: “A trained eye and mind and that almost carnal instinct for selling that is so difficult to acquire, but which can be cultivated and perfected”. Although the demands of life and profession led him to move to London, he has never completely severed the umbilical cord that links him to the Barcelona scene:

“The UK accounts for 23% of the global art market while Spain, as a whole, doesn’t even come close to 1%. But if there’s one thing I’ve learnt, it’s that it’s possible to do gallerism and promote cultural activity from the periphery of the periphery”.

In this sense, Barcelona can bring to the world “modernity and cosmopolitanism within a very solid local tradition. Joan Miró used to say that it is possible to have your roots deep in your own land and, at the same time, extend your branches towards the universe”.

The Future of Art

Homs is interested in contemporary art, beyond commercial phenomena and ephemeral fashions:

“Those artists who are capable of projecting an original and fertile gaze on the great debates in which we are immersed, from the gender perspective to the conservation of the planet or the psychological effect of pandemics and confinements”.

These are, in his opinion, the artists to whom we will have to turn in a few decades “to understand these first years of the 21st century in the same way that the French novel explains the 19th century or the cinema explains the 20th century”. Sensitivity and creative talent, once again, as Ariadne’s threads with which to find one’s way through the labyrinth of reality.

Photographs taken by Horse and lent by Llucià Homs.